On 7 October, 50 years after the Yom Kippur War, several Palestinian militant groups led by Hamas launched a coordinated offensive against the nearby Israeli cities, Gaza border crossings, and adjacent military installations. Some 1,200 Israelis and foreign nationals, mostly civilians, were brutally killed and 240 taken hostage. The attack triggered Israel’s mass mobilisation and lethal counteroffensive.

By mid-December, over 20,000 Palestinians, some 70 percent of whom women and children, are likely to be killed (although these figures are likely to be gross underestimations) and 1.9 of the 2.3 million Palestinians displaced. If the Israeli offensive would last a year, which is the tacit goal of Israel’s far-right government,over 100,000Palestinians would be dead by October 7, 2024. As talks continued on hostage deals and hundreds of thousands marched for peace in world capitals, the war has continued, despite a truce and loud calls for lasting ceasefire.

It is a dramatic narrative. But it is about theproximatecauses of 7 October, which has been in the cards for years.1In late October, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said that “nothing can justify the deliberate killing, injuring and kidnapping of civilians,” adding that “Hamas did not happen in a vacuum.”2It was an effort at balance, one that was soon misrepresented by partisan fanatics.

What follows is the story of this “vacuum”. An outline of theultimatecauses; that is, extremist settler terror and missed opportunities of peace, long-standing ethnic cleansing and the effort to control huge offshore oil and gas reserves.

Rise and demotion of the peace movement

After the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel occupied the West Bank and East Jerusalem, Gaza, and the Golan Heights. Since then, Israel has allowed and encouraged its citizens to live in these settlements, which are motivated by religious, ultra-ethnic and ultra-nationalist sentiments.

At the eve of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, I toured in these Occupied Territories and interviewed both the colonisers and the colonised. What I found most ominous was the gap of perceptions between the two. The Israelis saw a bright future and thought they were paving the way to a lasting peace. The Palestinians saw no future and dreamed of a land of their own.

After the 1973 War, Israel’s Labour coalition began to intensify the expansion of the boundaries of Jerusalem eastward. This encouraged a group of Messianic settlers to create a foothold in the West Bank, including Ma’ale Adumim by the Gush Emunim. These religious far-right Jews were met with protests by the peace activists.3

Among the peace movement’s leaders was Yael Dayan, the daughter of General Moshe Dayan, and a future Labour politician and feminist. Like in 1973, she said recently that “there cannot be a real and lasting peace that can be reconciled with the massive colonisation”.4After discussions with her, I joined the movement and the protests. I saw the settlements as a ticking time bomb that could subvert Israeli democracy, endanger its Jewish and Arab citizens and Palestinians, morph into apartheid, and cause a cycle of “forever wars” with its Arab neighbours.

One of the founders of the “Peace Now” movement was the late novelist Amos Oz, a dear friend whose book on the settler-induced divisionsIn the Land of Israel(1983) I would later translate. He was among the first Israelis to advocate a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Oz warned of the dangers of the occupation already back in 1967 when he called the radicalised settlers neo-Nazis (figure 1).

Legitimation of far-right extremism

In the early ‘70s, the settlers were in the margins of the society. Last December, they entered the government. By summer, the ex-chief of Mossad Tamir Pardo (2011-16) charged prime minister Netanyahu for bringing parties “worse than the Ku Klux Klan” into his government5(figure 2).

Since the tumultuous ‘70s, far-right politics, violent Messianic settlers, and ultra-nationalists like Rabbi Meir Kahane’s Kach have given rise to extremist movements, massacres of Palestinians, and political parties like Otzma Yehudit (“Jewish Power”), Kach’s ideological successor. Its leader, Itamar Ben-Gvir, first gained national notoriety in 1995 by brandishing a Cadillac hood ornament that had been stolen from Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. “We got to his car, and we’ll get to him too,” Ben-Gvir said.6Weeks later, Rabin, the architect of the peace process, was assassinated.

As Netanyahu’s minister of national security, Ben-Gvir has espoused Kahanism. As a settler, he lives in an illegal settlement. He has openly called for expulsions of Arab citizens. His provocative visit to the Temple Mount, the locale of al-Aqsa Mosque, contributed to the turmoil, as do recent efforts to replicate such visits.7

Another fatal decision of the Israeli government was the pledge of the energy minister Israel Katz that no “electrical switch will be turned on, no water hydrant will be opened and no fuel truck will enter Gaza” until the hostages would be free.8Reminiscent of Nazi practices, such collective punishments are morally repulsive and counterproductive in practice. When revenge massacres are imposed on innocent civilians, they breed new resentment, bitterness, and resistance.

Through his 20 years of participation in Israeli cabinets, Katz has fought for more resources for settlements. Opposing any two-state solution, he pushes for the annexation of the West Bank and wants to make Gaza Egypt’s headache.

Netanyahu’s Minister of Defence is Bezazel Smotrich, a vehement opponent of a Palestinian state, and self-proclaimed fascist, racist, and homophobe, who also lives in an illegally built West Bank settlement. In 2021, he declared that Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, should have “finished the job” and kicked all Palestinians out when Israel was founded. In his view, members of Israel’s Arab minority communities are citizens, but only “for now”.9

These are the hollow men in Netanyahu’s government. Neither they nor their peers will ever support policies recognising the sovereign and human rights of the Palestinians. Their ultimate objective is to expunge them. So, when Smotrich was entrusted with much of the administration of the occupied West Bank, the fox took over the hen house. It was a signal to Palestinian Arabs:Leave!

From Kahane’s terror to Sadat-Rabin assassinations

Among the peace activists, the concern in the ‘70s was that if the Messianic far-right Jewish settlers, many of whom came from the US, would be permitted to create a substantial de facto presence, it would be legitimised over time by de jure measures.10

In the 1980s, Gush Emunim radicalised further, forming the Jewish Underground, a radical terrorist organisation. Its launch was sparked by the Camp David Accords that led to the Egypt-Israel peace treaty in 1979, which the movement vehemently opposed, and the settlement project itself, which brought the far-right Messianic Jews in close proximity with the Palestinian communities.11It was a recipe for massacres.

The Underground conducted vicious terror attacks, including car bombs against Palestinian mayors, and plotted to blow up the Dome of the Rock at the centre of the al-Aqsa mosque.12The objective of the terror was to intimidate and bully the Palestinians out of the Occupied Territories.

I learned about these extremist trajectories during a mid-‘70s meeting in Jerusalem with the US-born Rabbi Meir Kahane, the far-right ultra-nationalist politician and later a member of the Knesset until his conviction for terrorism. Interestingly, the fanatically anti-communist Kahane had served as an informant with the FBI in the McCarthyite 1950s.13Having co-founded the far-right Jewish Defense League in the US, he established the ultra-radical Kach in Israel. Both used terror to advance their aims. By the ‘70s, Kahane promoted ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. “Israeli Arabs are moving closer to becoming a majority. Israel should not be committed to national suicide.” In his view, Palestinians had to go.

I had never met anyone as full of hate. Kahane couldn’t even utter the word “Arab” without a hint of disgust. I fully expected him to die in violence (figure 3).

Fast-forward to November 1990. As I was walking to Grand Central in mid-town Manhattan, I heard shots and saw a man running with cops behind him. Kahane had been assassinated. But his spirit lived on. A few years later, Binyamin Netanyahu, then-head of the opposition, contributed to the incendiary political climate where protesters branded prime minister Yitzhak Rabin a “traitor”, “murderer”, even “Nazi” for signing a peace agreement with the Palestinians. Then, Yigal Amir, a Jewish zealot, assassinated Rabin. He was linked with extremists influenced by Kahanism.

Like the Hamas offensive, the assassination was initially attributed to an “intelligence failure”. Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security, could have stopped the killer in advance, but didn’t.14 So, was the assassination “allowed” to happen, the critics asked?

In a historical view, Rabin’s assassination was the Israeli mirror-image of the prior Sadat’s assassination, which has been attributed to the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, whose members later figured among the fedayeen in Afghanistan that were armed, trained, and financed by the CIA’s Operation Cyclone.15(figure 4).

The assassinations’ message to peacemakers was loud and clear:Don’t even try!

Secret memorandum on the Gazan population transfer

Barely a week after the Hamas attack on 7 October, Israel’s Intelligence Ministry prepared a secret memorandum. It is this Ministry that oversees the Mossad and the Shin Bet, under the prime minister. In the 10-page memo, three options regarding the Palestinian civilians were predicated on “the overthrow of Hamas” and the “evacuation of the population outside of the combat zone”:

- Option A: Population remains in Gaza under Palestinian Authority,

- Option B: … but under local Arab authority.

- Option C: Population is evacuated from Gaza to Sinai.16

Of these three options, the memo recommended C, the forcible transfer of Gaza’s 2.3 million residents to Egypt’s Sinai, as the preferred course of action. In the Ministry’s view, Egypt, Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Canada would support the plan financially, or by taking in Palestinian refugees as citizens.

Two weeks later, the memo was leaked to the media.17It sparked an international firestorm over the “advocacy for ethnic cleansing”. Yet, the option was promoted by the Intelligence Minister Gila Gamliel, who claimed that members of the Knesset across the political spectrum were backing it.18In regional view, it was a pipe dream nobody bought.

Certainly, the early stages of Israel’s counteroffensive, “Operation Iron Swords”, reinforced the view that a population displacement is now at the forefront. Two days after the Hamas offensive, IDF Spokesperson Daniel Hagari stated that “the emphasis is on damage and not on accuracy”.19What followed was the Israeli army’s expanded authorisation for bombing non-military targets, the loosening of constraints regarding expected civilian casualties, and the use of an artificial intelligence system to generate more potential targets than ever before. The presumably “targeted” killings have absolutely nothing to do with ground realities as Gaza has morphed into a “mass assassination factory”.20Almost half of the Israeli munitions dropped on Gaza have been imprecise “dumb bombs,” US intelligence has acknowledged.

As Prime Minister Netanyahu struggled to downplay the memo, the leak worsened Israeli-Egyptian tensions. Meanwhile, a pro-Likud think-tank outlined “a plan for resettlement and final rehabilitation in Egypt of the entire population of Gaza”.21

But, truth be told, the transfer option isn’t exactly news. In Israel, such agendas had been disclosed already over three decades ago, and they were first implemented decades before.

Ethnic cleansing since 1947

Since the late 1980s, Israeli “new historians”, including Benny Morris, Ilan Pappé, Avi Shlaim, and Simha Flapan, have revised Israel’s role in the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight. In contrast to their precursors, they argued that ethnic cleansing triggered what the Palestinians call the Nakba (“Catastrophe”); that is, the displacement and dispossession of Palestinians, and the devastation of their societ.. Even prior to these historians, the Nakba had been described as ethnic cleansing by many Palestinian scholars such as Rashid Khalidi, Adel Manna, and Nur Masalha.

What divided the Israeli new historians was the question of whether the catastrophe was intentionally planned or collateral damage of the 1947 UN Partition Plan and the 1948 Israeli Independence. The damage idea was promoted by Benny Morris; the intentional interpretation by Ilan Pappé.22Morris relied primarily on Hebrew sources, while Pappé used both Hebrew and Arabic sources.

In light of historical evidence, ethnic expulsion has accompanied Jewish colonisation in Palestine ever since the 1880s and the beginning of the modern Zionist movement, as Pappé has argued with documentation. These expulsions were not decided on an ad hoc basis, as mainstream historians claimed. Instead, the Palestinian displacement and dispossession constituted ethnic cleansing, in accordance with thePlan Dalet(Plan “D”), drawn up in 1947 by Israel’s future leaders, such as David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of the nation. In this view, the aim has always been, and still remains, “to take over as much of Palestine as possible with as few Palestinians as possible”.23

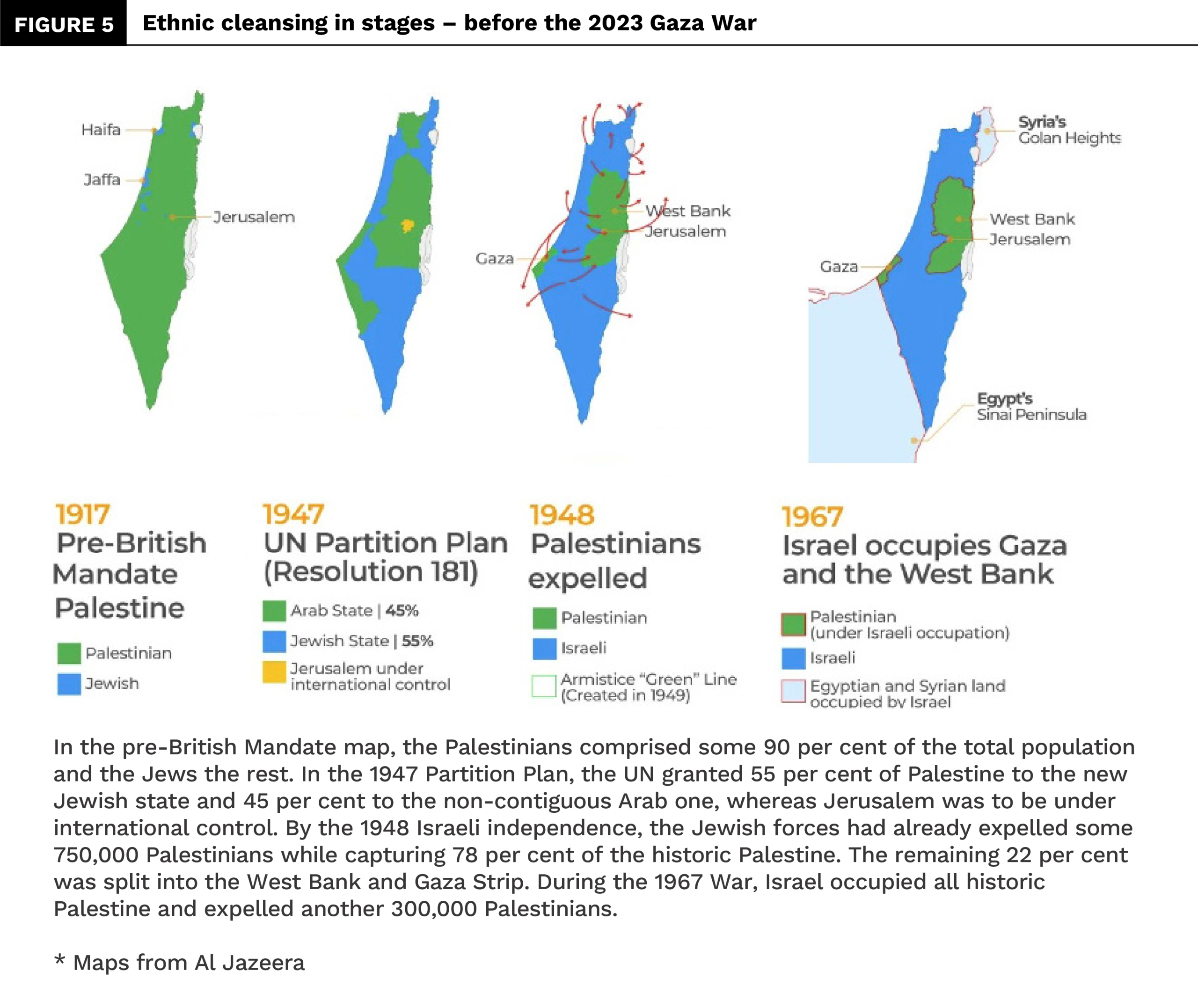

Today, the Palestinians in Israel, Occupied Territories, neighbouring Arab countries, and worldwide are the descendants of the 720,000 out of 900,000 Palestinians who once lived in areas that became Israel (figure 5).

After a month of systematic devastation in Gaza, Netanyahu’s far-right defence minister Smotrich stated that the “voluntary migration” of Palestinians in Gaza is the “right humanitarian solution”. Israel would no longer put up with “an independent entity in Gaza”. Meanwhile, Netanyahu lobbied European leaders to help him persuade Egypt to take in refugees from Gaza, without any success, even while he was downplaying his own Intelligence Ministry’s preferred proposal to “evacuate” all Palestinians. By contrast, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry said his country rejected any attempt to justify or encourage the displacement of Palestinians outside Gaza.24

In the UN Security Council, ethnic cleansing was defined in 1992 as “a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas”.25

It is this kind ofdemographicdisplacement that has motivated the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians, particularly since 1947. But the current efforts at population transfers, whether from Gaza or the West Bank, are no longer dictated by only demographic goals. Since the 1990s, ethnic cleansing seems to have also been motivated byeconomicobjectives.

$644 billion energy reserves

In the late 1990s, the Palestinian Authority (PA) contracted British Gas (BG) to develop the confirmed oil and gas fields of offshore Gaza. With its natural gas industry, Egypt would serve as the on-shore hub and transit point for the gas. BG pledged to finance the development and operation of the resulting facilities in exchange for90 per cent of the revenues, whereas PA would receive just 10 per cent, plus access to adequate gas to meet their needs.26But Israel, too, wanted a cut.

In 1999, Prime Minister Ehud Barak deployed the Israeli navy in Gaza’s coastal waters to impede the PA-BG deal. Israel demanded the gas to be piped toitsfacilities at a below-market-level price and control of all the revenues destined for the Palestinians, presumably to prevent the monies from being used to “fund terror”.27

After 2006, when Hamas triumphed in Gaza’s democratic election, it triggered the surreal intervention by British PM Tony Blair, who proposed the old deal structure, with the exception that the gas would be delivered to Israel, not Egypt, and the funds would first be delivered to the Federal Reserve Bank in New York for future distribution, again presumably to preempt financing of terrorist attacks.28

The two pretexts killed the limited Palestinian budget autonomy, along with the Oslo Accords, as a path was paved for future wars, which would then be blamed on Palestinians as well. And when the Hamas-led Palestinian unity government refused the impossible offer, Israeli PM Ehud Olmert imposed a blockade on Gaza. The “economic warfare” was expected to result in a “political crisis” and uprising against Hamas. Israel put the Palestinians “on a diet, but not to make them die of hunger”.29

Hence, the launch of Israel’s 2006 Operation Cast Lead to subject Gaza to a “shoah” (Hebrew forHolocaust), as Deputy Defence Minister Matan Vilnai warned. The idea was to “send Gaza decades into the past”, said commanding general Yoav Galant, Netanyahu’scurrentdefence minister who now pledges to “wipe this thing called Hamas off the face of the earth”.30

The operation did cause devastation in Gaza but failed to transfer the control of the gas fields to Israel. And as the West was swept by the Greater Recession in 2008-9, the new Netanyahu government found itself struggling with an energy crisis that became severe with the Arab Spring as Israel lost 40 per cent of its gas supplies.

With energy prices soaring, Israel witnessed the largest mass protests in decades.

Ironically, Netanyahu’s government was saved by a discovery of a huge field of recoverable natural gas in the Levantine Basin, a largely offshore formation under the eastern Mediterranean. Israel claimed that “most” of the newly confirmed gas reserves lay within Israeli territory, which sparked the contrary claims by and increasing tensions with Lebanon, Syria, Cyprus, and the Palestinians. Based on the 2010 US Geological survey, the oil and gas in the Levant Basin amounted to 122 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil (figure 6).31

What are the economic stakes in this resource struggle? In 2023 US dollars, the value of these resources translated to $557 billion and $87 billion, respectively. That’s about $644 billion in total.32

But there was more at stake.

The $16-$55 billion Ben Gurion Canal

Located in Egypt, the Suez Canal connects the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez with the Mediterranean Sea. Some 12 per cent of the world’s trade passes through Suez on 18,000 ships a year. In March 2021, it was blocked for six days by a container ship that had run aground. What if there was an alternative pipeline?

In the mid-19thcentury, the British considered the proposal of a canal to the Red Sea via the Dead Sea. In the early 1960s, a secret and controversial US proposal involved 520 nuclear blasts to excavate through Israel’s Negev desert. The idea was kept secret through the Cold War until 20 October 2020, when the Israeli state-owned Europe Asia Pipeline Company (EAPC) and the UAE-based MED-RED Land Bridge inked a deal to use the Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline to move oil from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. Interestingly, this occurred justone month afterthe Abraham Accords on Arab-Israeli normalisation between Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain.

In April 2021, Israel announced that work on the Ben Gurion Canal would begin by summer. The construction was expected to take about five years and employ 300,000 engineers and technicians. With estimated costs at $16 to $55 billion, the canal was expected to generate over $6 billion in annual income (figure 7).33

Following the global pandemic, the UAE, the host of the COP28 conference in Dubai, distanced itself from the controversial plan that Israeli environmentalists so vehemently opposed. The secretive EAPC had a dark environmental record. In 2011, it was responsible for Israel’s worst nature-reserve disaster; in 2014, for its worst environmental disaster.34Oddly, in January, the Netanyahu cabinet extended secrecy for EAPC, despite objections. As traffic at the EAPC’s terminal on the Gulf of Eilat surged in July, activists warned of an impending disaster.35

By 7 October, the only thing that stood between the Netanyahu government and the massive canal project was Gaza. Hence, the concerted effort to undermine the Palestine Authority, which in the 1990s still controlled Gaza, an attempt that began with Netanyahu’s gamble, in parallel with efforts to take over the offshore energy reserves and the proposed canal-building.

Hamas and Netanyahu divide-and-rule ploy

With a population of over 2 million on some 365 square kilometres, the Gaza Strip is one of the world’s most densely populated areas and “largest open-air prison”. After the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, it became an Egyptian-administrated territory. Following the 1967 Six-Day War, it came under Israeli occupation.

The precursor of Hamas, Al Mujamma al Islami (“The Islamic Centre”), was established in Gaza in the 1970s under the auspices of the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood.36One of their adherents was the wheelchair-bound Sheik Ahmed Yassin, the future leader of Hamas. Yassin concentrated the Mujamma’s activities on religious and social services. Ironically, Israeli authorities supported its rise, when their main antagonist was still the late Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO). So, while PLO operatives in the Occupied Territories faced brutal repression, the Islamists affiliated with Egypt’s banned Muslim Brotherhood could operate in Gaza. Israelis were using the Islamists against the PLO.37

Yassin was jailed in 1984 on a 12-year sentence, but released only a year later. At the time, Netanyahu served as the Israeli ambassador to the UN. I interviewed him about hisFighting Terrorism(1986), which offered lessons on “how democracies can defeat domestic and international terrorists”. Smart and slick, he represented a new generation of Israeli politicians trained by American PR experts and his former employer, global consultancy BCG.

Hamas was manna from heaven to Netanyahu. Launched in 1988 amid the first intifada (uprising), it has always refused to accept the existence of the Israeli state. When the peace process began between Rabin and Arafat, Yassin was in prison. Hamas launched a campaign of attacks against civilians, which contributed to the rise of Netanyahu and the Israeli conservatives, and the far right in 1996 (figure 8).

As prime minister, Netanyahu ordered Yassin to be released from prison (“on humanitarian grounds”), despite a life sentence. He relied on the Islamists to sabotage the Oslo Peace Accords. After having expelled Yassin to Jordan, Netanyahu allowed him to return to Gaza as a hero in late 1997. Until his killing in 2004, Yassin initiated a wave of suicide attacks against Israelis. Yet Netanyahu told his Likud Party’s Knesset members in March 2019 that “anyone who wants to thwart the establishment of a Palestinian state has to support bolstering Hamas and transferring money to Hamas. This is part of our strategy: to isolate the Palestinians in Gaza from the Palestinians in the West Bank.”38

In the 1990s, as part of the Oslo Accords, most of Gaza had been handed over to the Palestinian Authority, alongside the Israeli settlements, which were evacuated in 2005, despite intense opposition by the Israeli far right. Two years later, after an election victory that rankled with both the West and the PLO, Hamas began administering Gaza. That led both Israel and Egypt to impose a land, sea, and air blockade, which devastated Gaza’s ailing economy.

From economic blockade to military destruction

By 2021, Gaza’s economy was on the verge of collapse.39Even before the global pandemic, the Palestinians organised widespread protests demanding that Israel end the blockade and address the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. All protests proved futile.

The final solution of Netanyahu government’s far right seems to be the devastation of Gaza and the twisted hope that this would cause a mass emigration of Gazans away from the Israeli border. Hence, the preference for theDahiya Doctrine, outlined by former IDF Chief Gadi Eizenkot in the 2006 Lebanese War and in the 2008-9 Gaza War. It is premised on the destruction of the civilian infrastructure of “hostile regimes”:

What happened in the Dahiya quarter of Beirut in 2006 will happen in every village from which Israel is fired on… We will apply disproportionate force on it and cause great damage and destruction there. From our standpoint, these are not civilian villages, they are military bases.40

Scholars of international law call it “state terrorism”.41In the view of the UN, it was a “carefully planned” assault intended “to punish, humiliate and terrorise a civilian population”.42In Gaza, it looks increasingly like a war crime of historical magnitude. Yet, after 7 October, Eisenkot was appointed as a minister without portfolio in Netanyahu’s war cabinet.

The international media have been widely and often rightly criticised for the lack of impartiality in reporting. As an old adage puts it, “the first casualty when war comes is truth”. In Gaza, truth has also been a strategic target, judging by the extraordinary number of journalists killed.

As of December 14, investigations by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) showed 63 journalists and media workers had been killed in some two months. Nine out of 10 were Palestinian, the rest Israelis and Lebanese. It was the deadliest time for journalists ever since the CPJ began gathering data in 1992.43

Yet, international media organisations continued the flawed, surreal rhetoric about “targeted bombing” designed to “minimise the casualties”.

West Bank’s apartheid and settler violence

On 12 October, just days after the Hamas attack, Israeli soldiers and settlers detained three Palestinians from the West Bank village Wadi as-Seeq. For hours, the Palestinians were severely beaten, stripped to their underwear, and photographed handcuffed, in their underwear. The captors urinated on some and extinguished burning cigarettes on others, while trying to penetrate one of them with an object.

Soldiers and settlers also arrested leftist Israeli activists who were present, cuffed and threatened to kill them, and detained them for hours. Both groups were robbed.44

It would be naïve to explain away such incidents as anomalies. The brutal bullying, the lawless harassment, the collusion of police, military, and settlers, the inhuman treatment – these are all reminiscent of black segregation in South Africa. Based on white supremacy and racial segregation, the system of apartheid was in place from 1948 until 1994. Today, a similar system prevails in the West Bank. Netanyahu’s government seeks to annex the West Bank, which threatens the prospects for a just and lasting resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.45

Like the Israeli peace movement, the international community considers the settlements a violation of international law.46But in the absence of effective enforcement, lofty rhetoric has long been a part of the problem. The writing has been on the wall since the 1970s. With settlement expansion, it has turned both bloody and devastating.

In 2015, the former head of Shin Bet, Yuval Diskin, warned that “alongside the State of Israel, a de facto State of Judea is being formed” in which “there are different standards, different value systems, different attitudes towards democracy, and there are two legal systems”. Meanwhile, “anarchistic, anti-state, violent, and racist ideologies… are treated tolerantly by the Israeli legal and judicial system.” He criticised the Netanyahu government for turning a blind eye to “Jewish terrorism”.47

Half a decade later, Human Rights Watch warned that Israel had crossed the apartheid threshold.48Farsighted Israeli leaders no longer deny the reality of apartheid. Last year, former attorney general Michael Ben-Yair called Israel “an apartheid regime”. In early September this year, even the ex-chief of Mossad, Tamir Pardo, said that Israel’s mechanisms for controlling the Palestinians matched the old South Africa. “There is an apartheid state here,” since “two people are judged under two legal systems”.49

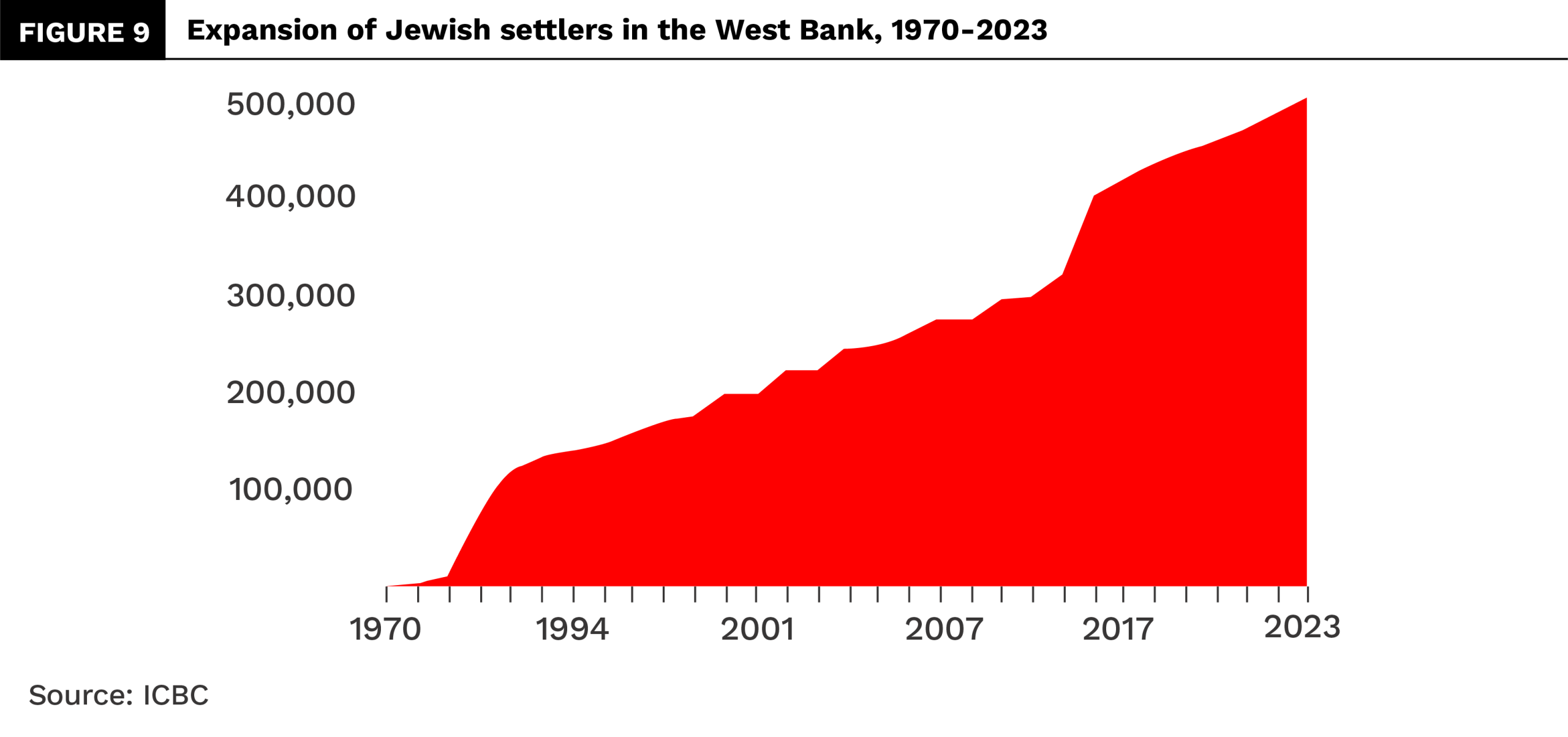

Long before the Hamas offensive, Palestinian stagnation reflected economic ruin that was excessive even relative to apartheid South Africa. Today, the Palestinians’ per capita income in comparison to Israelis is lower than that of the blacks relative to the whites in apartheid South Africa.50Even before the current war, the Gazans’ position was even worse, far worse. Furthermore, talks for a two-state solution have been stalling since 2014. As a result, nothing has halted the settlers’ steady expansion since the late 1960s (figure 9).

While Gaza is being eradicated, things are getting a lot worse in the West Bank. As international media focused on the Israeli ground assault in Gaza, Zvi Sukkot was appointed chairman of the Knesset Subcommittee for Judea and Samaria (West Bank). Inspired by Kahane, the ex-member of the Jewish terrorist groupThe RevoltSukkot has advocated dismantling the state of Israel to establish a Jewish Kingdom, a Judaic theocracy following Jewish Law. He has allegedly participated in a mosque arson, violence against Palestinians, protests against Shin Bet, and demolition of homes. Now he is making his dreams true, seemingly democratically.

In the early 1970s, there were barely 2,000 settlers in the West Bank. Today, that figure exceeds 500,000. Their problem is that they will never win the peace.

Rise of US military aid, plunge of Israeli labour

During the early days of independence, Israel’s politics was dominated by Labour alignments from David Ben-Gurion to Golda Meir. In 1949, the Labour alignment (46) and the left (25) had over 70 seats in the 120-member Knesset. Despite a near monopoly, the alignment still held over 60 seats in 1973, with Labour increasing its voice and the left losing half of its seats. Yet, today the Labour coalition has lostmore than 90 per centof its representation some 75 years ago (figure 10).

The debate on the decline of Israeli Labour is long-lasting.51Usually, the losses are attributed to the failure of the Oslo Accords to make Israelis feel more secure, the inability of the alignment to attract Labour voters, the failure to stay attuned to demographic shifts, and the decline of social democratic parties in Western Europe.

Most analysts fail to associate the parallel trends of the plunge of Israeli Labourandthe rise of US aid. Even the air triumphs of the Six-Day War were still premised on the French-made Mirage and Super Mystère jets. The US economic and military aid soared only after the 1973 War. Until 2002, Israel was the top recipient of US aid and it has stayed among the top three with Iraq, Afghanistan, and Ukraine.

The US has given Israel over $260 billion in military and economic aid, plus $10 billion for missile defence systems. In 2017, the bilateral tie entered a new era as Israel and the US inaugurated the first American military base on Israeli soil, 25 kilometres from Gaza. The US base would deploy Iron Dome to defend against short-range rockets. On 7 October, Hamas soldiers came within a few kilometres of the airfield.

Just weeks before, the Pentagon awarded a multimillion-dollar contract to build US troop facilities for a secret base deep within Israel’s Negev desert, also close to Gaza. Code-named “Site 512”, it is a radar facility that monitors the skies for missile attacks on Israel.52Ironically, on 7 October, Site 512 saw nothing. When rockets burst from Gaza, it was focused on Iran.

In brief, the Pentagon is taking steps to fortify Israel, but mainly initsown Middle East geopolitics, which also involves increasing presence in Lebanon, in close proximity to offshore energy reserves.

Neoliberalism and Israel’s economic erosion

Netanyahu has long advocated neoliberal policies. Since January, his government has also pushed for highly controversial judicial reforms, a series of changes to the judicial system and the balance of powers. The amendment was passed by Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, in late July. The judicial effort reflects descent toward autocracy and was opposed by most Israelis in massive protests.

Behind these judicial reforms looms the Kohelet Forum, an ultra-conservative think-tank partly funded by two Jewish-American billionaires, Arthur Dantchik and Jeffrey Yass. The key financier behind Netanyahu has been the late casino mogul Sheldon Adelson, whose monies have also boosted Rabbi Meir Kahane’s disciples in Israel. In 2019, the US appeals court revived a $1 billion lawsuit by Palestinians seeking to hold Adelson and other pro-Israel defendants liable for alleged war crimes and support of Israeli settlements.53

Netanyahu has led six Israeli cabinets in the past 25 years. He remains haunted by a litany of bribery, fraud, and breach of trust charges. To avoid prosecution, he needs to stay in power.

Thanks to his neoliberalism, Israel has exceptionally high inequality compared to other OECD countries, despite its early socialism. After a remarkable recovery from the pandemic, the risk balance in Israel is tilted to the downside.54The war compounds the risks. Adding to its active military force of 150,000, the Israeli army has summoned 360,000 additional reservists, 8 per cent of Israel’s workforce, for the war on Gaza, which costs Israel $260 million a day.

Long-term trends are alarming. Half a yearbeforethe hostilities, 280 senior economists warned that the government’s budget allocations to the ultra-religious Haredi groups, in exchange for their coalition support, “will transform Israel in the long run from an advanced and prosperous country to a backward country”.55The economic backlash associated with the proposed judicial overhaul had led to a massive capital flight and sharp decline in foreign investment, resulting in currency depreciation, a sluggish stock market, a slowdown in tax revenues, and rising public debt.56

Recently, the Bank of Israel warned that war was a “major shock” to the economy and more expensive than estimated.

Risk of regional escalation

Regionally, the war has led Biden’s hawks to refocus attention to Iran, once again. Since 2003, the US Army has conducted an analysis called TIRANNT (Theater Iran Near-Term) for a full-scale war with Iran.57Predictably, the war has inflamed tensions with Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon, which many in the Congress would like to link with Gaza, despite no evidence of Iran’s direct involvement. To Netanyahu’s government, an Iran conflict would divert attention from Gaza and the West Bank.58

The ongoing war has severely undermined US credibility as a neutral broker in the region. Officially, Washington seeks to de-escalate tensions. In practice, US diplomats have been discouraged from publicly using phrases that would urge calm.59Washington’s bipartisan consensus is driven by the Pentagon and Big Defence, which profit from every new major conflict, by selling security without peace, as illustrated by Blinken’s own think-tank.60

The Gaza War is a textbook case. In the first six days of its counteroffensive, Israel dropped 6,000 bombs on Gaza. That’s almost the number of bombs the US droppedin an entire yearon Afghanistan, which is 1,800 times larger than Gaza.

What the region needs is multilateral cooperation and multipolar diplomacy. After $8 trillion in the misguided post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the US war theatres have not disappeared. It’s only their arenas that are shifting.

Intelligence failure – or not

Recently, theNew York Timesreported that “Israel knew Hamas’s attack plan more than a year ago”. Code-named “Jericho Wall”, the 40-page blueprint outlined the kind of lethal invasion that resulted in the death of some 1,200 Israelis. The document was circulated widely among Israeli military and intelligence leaders, but experts determined that an attack of that scale and ambition was beyond Hamas’s capabilities.61

TheTimesreport reverberated internationally. But it wasn’t a scoop. Soon after 7 October, the Israeli media releasedseveralcritical pieces indicating that many intelligence analysts’ warnings were ignored. What was new in theTimespiece was the blueprint document. Underpinning all these ignored warnings was the flawed belief that Hamas lacked the capability to attack and would not dare to do so.

This belief was fostered by two tacit factors. First, gender bias and sexism. The longer that militarisation has prevailed in Israel, the more the country’s gender gap has deepened. Today, Israel ranks at the level of El Salvador and Uganda in this regard.62Since 7 October, testimonies from members of mainly female look-out units have bolstered accusations that Netanyahu’s leadership fatally misread the dangers from Gaza. Not just Netanyahu, but senior politicians from across the political spectrum bought into the idea, which was also touted by the Israel Defence Forces and eventually Shin Bet. “It’s infuriating,” said Maya Desiatnik soon after 7 October. “We saw what was happening, we told them about it, and we were the ones who were murdered.” She is from Nahal Oz, where 20 other women border surveillance soldiers were murdered by Hamas.

Second, half a century of occupation has left an impact not just on popular opinion but on analytical assessments. The idea that Hamas lacked the capability to attack was predicated on the notion that “they” wouldn’t be as imaginative as “we” can be. Based onone or two years of evidence, Hamas militants trained for the brutal attacks in at least six sites across Gaza in plain sight and less than 1.5 km from Israel’s heavily fortified and monitored border, as even CNN reported in early October.63

Worse, many testimonies by Israeli witnesses to the Hamas attack add to growing evidence that the Israeli military killed its own citizens as it struggled to neutralise Palestinian gunmen. As one witness said to Israel Radio: “[Israeli special forces] eliminated everyone, including the hostages.”64

In the 1980s, the Operation Cyclone led the US to train, arm, and finance a generation of Islamist fedayeen in Afghanistan, including Osama Bin Laden. Netanyahu’s governments thought they could exploit Hamas, not that Hamas could exploit them.

But if the intelligence failure wasn’t a failure at all, what was it?

“Slaughter and Carnage by Another Name”

From the start, Israel’s counteroffensive has relied on a rhetoric of targeted killing, but with actual focus on the destruction of Gaza. In the view of the Israeli military, their operation comprises tactical military targets – underground targets such as tunnels, but particularly power targets like high-rises and residential towers, and operatives’ family homes. In past wars, military and underground targets were in the key role. Now it belongs to power and family-home targets. The real objective is maximum harm to Palestinian civil society.65

What about the damage? There are an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 members of Hamas. As of mid-December, 2023, some 3,000 to 5,000 had been killed (7,000 according to Israeli sources); that is, about 7 to 15 per cent. Meanwhile, 1.9 million Palestinians had been displaced, almost 80 per cent of the total. Some 19,000 people have been killed and 50,000 injured, and thousands remain missing, two-thirds of them women and children. More than 60 per cent of the homes and residential units have been destroyed; and with them, most hospitals. And with the collapse of health systems, misery and vice will follow in due time, in the form of famine and epidemics.

Is it a prelude to the West Bank?

There are almost no Palestinians remaining in the vast area stretching east from Ramallah to the outskirts of Jericho. Most of the communities who lived in the area have fled for their lives in recent months as a result of intensifying Israeli settler violence and land seizures, backed by the Israeli army and state institutions. Israeli settlers have chased out entire Palestinian communities in Area C,66an area that just happens to stand “above sizeable reservoirs of oil and natural gas wealth”, as UNCTAD stressed already in the late 2010s (see figure 6).

In the past, ethnic cleansing had mainly demographic objectives. Today, it also serves economic agendas. The consequent damage can no longer be consideredcollateralbutintended.

Ethnic cleansing and genocide resemble each other. Nevertheless, ethnic cleansing is intended primarily to displace a persecuted population from a given territory, whereas genocide is intended mainly to destroy a group. Most Israelis abhor the very idea of genocide, yet both ethnic cleansing and genocide go hand in hand with settler colonialism. Furthermore, the system of apartheid, including its most vicious forms, is already an acknowledged reality in the Occupied Territories.

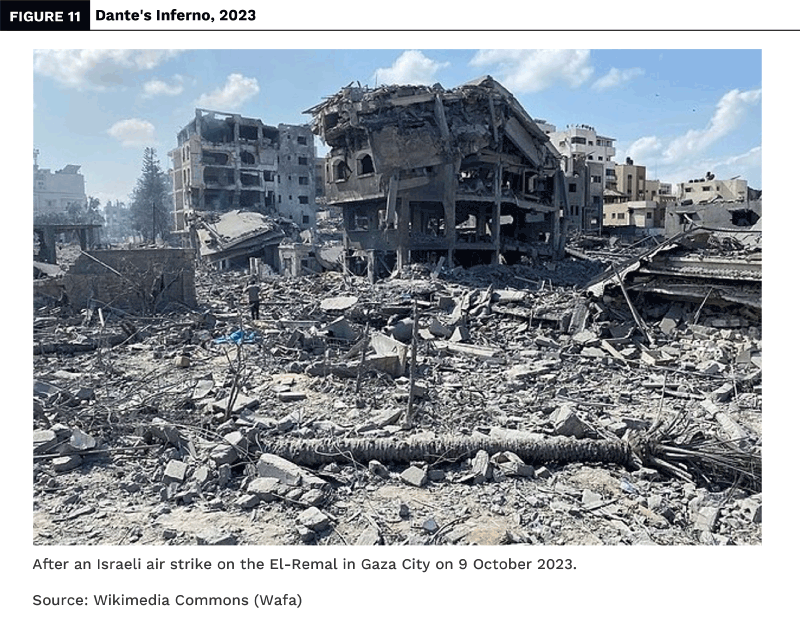

As Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva says, what’s happening in the Middle East “isn’t a war, it’s a genocide”.67Analytical distinctions are irrelevant to those who lose their loved ones, especially innocent children, in unwarranted wars that are just slaughter and carnage by another name (figure 11).

The prospect of the SecondNakba

The one thing that once stood between the Netanyahu government and the grandiose plans for a Greater Jewish Israel with abundant energy fields was Gaza. Hence, the frantic activity of the Biden administration and the subdued silence of Brussels. Both like the ensuing energy scenarios, but detest the bad PR.

Ultimately, it is these demographic agendas, deeply ingrained in decades of ethnic cleansing, that are now coupled with economic energy aspirations.

In this view, the Israeli intelligence didnotfail on 7 October. It did its job; it warned the policymakers about the impending threat. It’s the political leadership that failed. Intentional or not, this neglect serves the far-right government’s tacit political objectives to neutralise Gaza and Palestinian sovereignty by displacing the Gazans, and to advance preconditions for Palestinian expulsions from the West Bank.

There is a trade-off, though. The consequent Israel would no longer be the secular, Jewish-Arab democracy it was once supposed to become. Rather, it may trend toward a militarised, neoliberal Jewish autocracy that most Israelis intensely oppose, but American financiers prefer. Milton Friedmans need their Pinochets. The external chasm between Jews and Palestinians would be replaced by internal divides between rich and poor, secular and religious, Western and Eastern Jews.

Here’s the inconvenient truth: the First Nakba resulted from ethnic expulsions, most of which preceded Israeli independence in 1948. The Second Nakba would also be about sovereignty over gas and oil, should the international community allow it. And if it does, make no mistake about it, our humanity will no longer be the same.

What happens in Palestine won’t stay in Palestine.

About the Author

Dr. Dan Steinbock is the founder of Difference Group and has served at the India, China and America Institute (US), Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, seehttps://www.differencegroup.net/.

Views are personal

Stay updated with all the insights.

Navigate news, 1 email day.

Subscribe to Qrius