Daniel O’Gorman, Oxford Brookes University

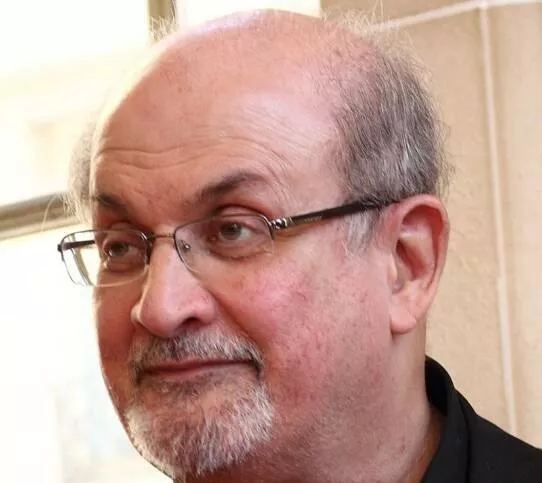

Rushdie is the author of 14 novels, most famously The Satanic Verses (1988). A sprawling magical-realist epic, the book sparked outrage among Muslims around the world due to its veiled representations of the Prophet Muhammad.

Upon its publication, protests broke out in India, the novel was banned, and footage of book burnings were widely broadcast around the world. Similar demonstrations took place in the UK, in places with large Muslim populations such as Bolton and Bradford.

On February 14 1989 (a date that Rushdie has sardonically described as his “unfunny Valentine”), Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa (or decree) against Rushdie, calling for his murder. The “Rushdie affair” became headline news around the world and the author was forced into hiding for most of the 1990s.

At present, it is not possible to comment on the specific motives of Rushdie’s alleged attacker, Hadi Matar, which are the subject of a legal investigation. However, we can begin critically considering how best to respond to this disturbing incident, which has been so long in the making.

Variations of offence

It’s hard to think of another novel over which so much blood has been spilt. News coverage of Rushdie’s novel has tended to emphasise its depiction of the Prophet Muhammad as the primary cause of offence. However, outside of the headlines, measured scholarly debate about the text’s perceived blasphemy has continued for over 30 years.

Postcolonial theorist Homi K Bhabha influentially suggested that the novel’s most subversive element isn’t its apparent depiction of Muhammad, but its placing of sacred material from the Qur’an into the secular context of a novel. This cultural translation challenges the Islamic belief that the Qur’an is the untranslatable word of God.

Meanwhile, the scholar of religion, Karen Armstrong, has explored the book’s theological background. Rushdie draws upon a contested segment of Qur’anic lore sometimes referred to as “the satanic verses”. In these verses, the Prophet Muhammad is alleged to have struggled to clearly distinguish between devilish deceit and divine revelation. The verses are controversial because they cast doubt upon Muhammad’s infallibility.

As literary critic Anshuman Mondal has argued, the framing of the Rushdie affair and its aftermath in the media has sometimes been troublesome. Representations of the novel as a battleground between free speech and Muslim fundamentalism belie a refusal to engage seriously with a reality that is more complex. What is lost in this characterisation is the fact that many Muslim readers hold conflicting, multi-faceted views about Rushdie and his text.

Free speech versus ‘fundamentalism’

So far, public commentary on the stabbing has overwhelmingly and rightly expressed concern for Rushdie’s wellbeing. There has also been unconditional condemnation of his assailant. Simultaneously, some of this commentary has begun to frame the incident using the familiar free speech versus fundamentalism binary.

The attack was undoubtedly an assault on free speech. However, recent scholarship on Islamophobia warns us that a collective eagerness to focus on Islamic extremism can lend itself to a perception of the world in which western-style liberalism is pitched simplistically against religious – and especially Muslim – “barbarism”. This sort of worldview, academics further warn, can lead to an increase in discrimination towards Muslims.

Horrific as this incident has been, it’s vital to avoid hyperbolic rhetoric about a “clash of civilisations”. We should also be wary about embracing the kind of free speech fundamentalism that French far-right figures like Éric Zemmour and Marine Le Pen have exploited in the wake of the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks.

Media studies academic Gavan Titley has argued that the invocation of “free expression” in recent liberal discourse has all too often served to enable racism. “An utterly hegemonic focus on Muslim ‘integration,’” he writes, “is presented as the equivalent of taking a stand against the 19th-century Catholic church, or Stalinist totalitarianism”. As scholars of Rushdie’s writing have long suggested, it is necessary to uphold free expression without reducing it to caricature.

In our rightful proclamations about free expression in response to this attack, we would do well to remember one of The Satanic Verses’ central motifs: “What is the opposite of faith? Not disbelief. Too final, certain, closed. Itself a kind of belief. Doubt.”

Daniel O’Gorman, Research Fellow in English Literature, Oxford Brookes University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Stay updated with all the insights.

Navigate news, 1 email day.

Subscribe to Qrius